Poet, essayist, and playwright Susan Griffin was born in 1943 in Los Angeles, California. An early awareness of the horrors of World War II and her childhood in the High Sierras have had an enduring influence on her work, which includes poetry, prose, and mixed genre collections. A playwright and radical feminist philosopher, Griffin has also published two books in a proposed trilogy of “social autobiography.” Her work considers ecology, politics, and feminism, and is known for its innovative, hybrid form. Her collections in this vein include

Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her (1978);

A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War (1982), which was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Award, won a BABRA Award, and was a

New York Times Notable Book;

The Eros of Everyday Life: Essays on Ecology, Gender, and Society (1995);

What Her Body Thought: A Journey into the Shadows (1999);

The Book of Courtesans: A Catalog of their Virtues (2001); and

Wrestling with the Angel of Democracy: On Being an American Citizen (2008). Her play,

Voices (1975), won an Emmy and has been performed throughout the world. She also co-edited, with Karen Loftus Carrington, the anthology

Transforming Terror: Remembering the Soul of Terror (2011). In addition to her numerous books on society and ideas, Griffin has written several volumes of poetry, including

Dear Sky (1971);

Like the Iris of an Eye (1976);

Unremembered Country (1987), which won the Commonwealth Club’s Silver Medal for Poetry; and

Bending Home: Selected and New Poems 1967-1998 (1988).

Griffin’s poetry is known for its minimalist style and interest in politics and the domestic.

Unremembered Country has been described as a poetic mosaic of female self-discovery. “All of the poems are written in a tightly controlled, minimal style,” commented Bill Tremblay in

American Book Review, “that witnesses to the most serious crises in our lives, even to the ‘unspeakable’ cruelties, while at the same time not becoming ‘another facet of the original assault.’“ Griffin’s prose collections also consider ideas of crises and feminism, and are frequently as combative as they are elegant. The magazine

Ms. described Griffin’s

Woman and Nature as “cultural anthropology, visionary prediction, literary indictment, and personal claim. Griffin’s testimony about the lives of women throughout Western civilization reveals extensive research from Plato to Galileo to Freud to Emily Carr to Jane Goodall to

Adrienne Rich… Griffin moves us from pain to anger to communion with and celebration of the survival of woman and nature,” the reviewer concluded.

eoffrey Hill’s ”Triumph of Love” is a book-length meditation on ”the fire-targeted century” now ending, an elegy for everyone who has burned. I say elegy, but in fact the poem is a carnival of literary kinds: it incorporates schoolboy gags, theological excursuses, radiant landscape pictures, mock litanies, epigrams, London music-hall routines and seething political satire. Hill rapidly shifts from one mode to the next as he proceeds through the poem’s 150 separate sections, some of which are as short as one line, some as long as a page and a half. The poem’s aim is to honor faith and innocence as embodied in victims of historical violence, above all the European war dead and the Jews of the Holocaust. It is an aim Hill has kept before him almost continuously since ”For the Unfallen” was published in 1959, the first of his eight books of poems. Always an exquisitely, even excruciatingly self-conscious poet, he now turns on himself with fresh intensity, interrogating his aims and means even as he defends them. One of the poem’s parodic voices (a stand-in for a public that would prefer to forget about its debts to the dead) wonders, ”What is he saying; / why is he still so angry?” The uncomprehending question is its own reply.

eoffrey Hill’s ”Triumph of Love” is a book-length meditation on ”the fire-targeted century” now ending, an elegy for everyone who has burned. I say elegy, but in fact the poem is a carnival of literary kinds: it incorporates schoolboy gags, theological excursuses, radiant landscape pictures, mock litanies, epigrams, London music-hall routines and seething political satire. Hill rapidly shifts from one mode to the next as he proceeds through the poem’s 150 separate sections, some of which are as short as one line, some as long as a page and a half. The poem’s aim is to honor faith and innocence as embodied in victims of historical violence, above all the European war dead and the Jews of the Holocaust. It is an aim Hill has kept before him almost continuously since ”For the Unfallen” was published in 1959, the first of his eight books of poems. Always an exquisitely, even excruciatingly self-conscious poet, he now turns on himself with fresh intensity, interrogating his aims and means even as he defends them. One of the poem’s parodic voices (a stand-in for a public that would prefer to forget about its debts to the dead) wonders, ”What is he saying; / why is he still so angry?” The uncomprehending question is its own reply.

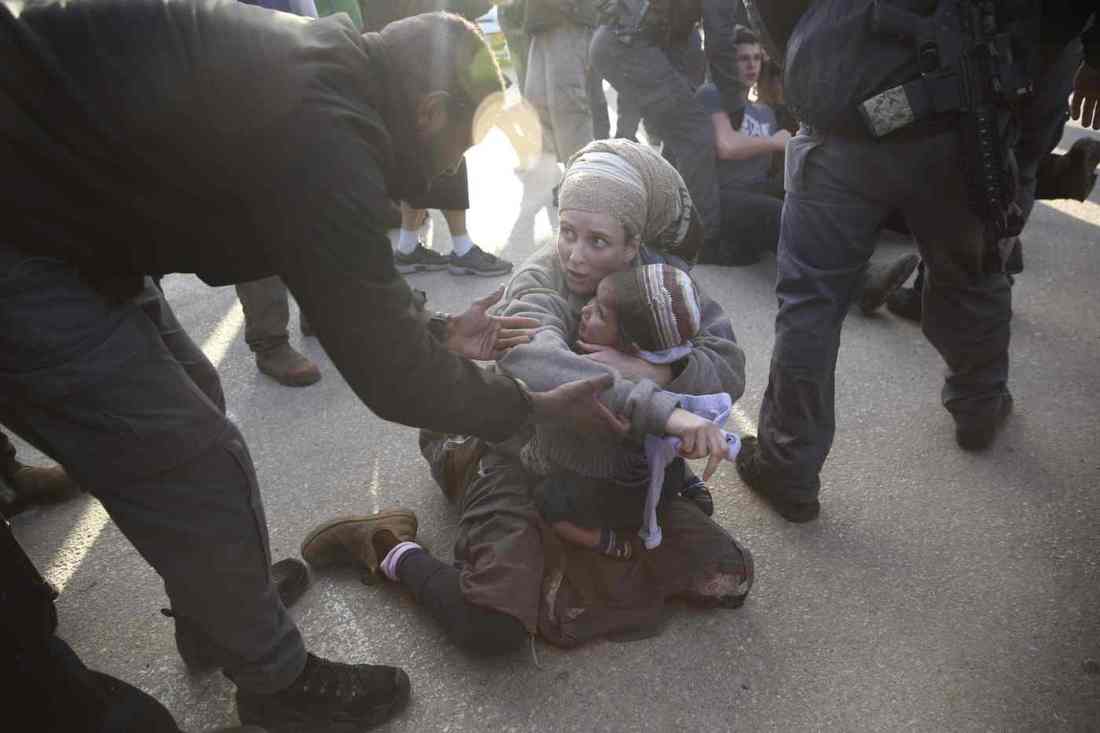

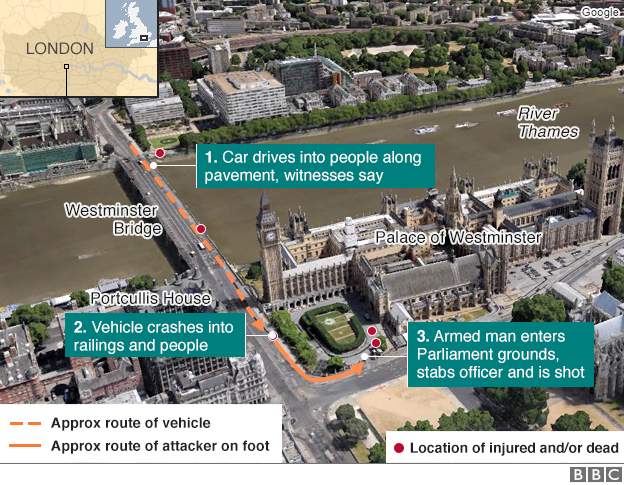

Photo by a friend.Copyright

Photo by a friend.Copyright